Dr. Sanoop Kumar Sherin Sabu M.D.,

Introduction

Hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) is one of the most common primary liver cancers and often occurs in the setting of chronic liver disease, particularly cirrhosis and chronic viral hepatitis (HBV, HCV). Early detection and management of HCC are critical in improving patient outcomes. This article aims to provide a comprehensive overview of the radiological findings and management protocols for hepatocellular carcinoma.

1. Radiological Findings in Hepatocellular Carcinoma

Radiology plays a pivotal role in the diagnosis and staging of HCC. Accurate imaging is essential for assessing tumor characteristics, extent, and potential treatment options. The following are the key radiological features that gastroenterologists should be familiar with:

1.1 Ultrasound (US)

- Role: Primary screening tool for patients at high risk for HCC (e.g., cirrhosis, chronic viral hepatitis).

- Findings:

- Detection of a mass or nodule in the liver parenchyma.

- Hypervascular lesions may appear as hypoechoic (darker) or hyperechoic (brighter) regions.

- Can detect features of cirrhosis (e.g., nodular liver contour, splenomegaly).

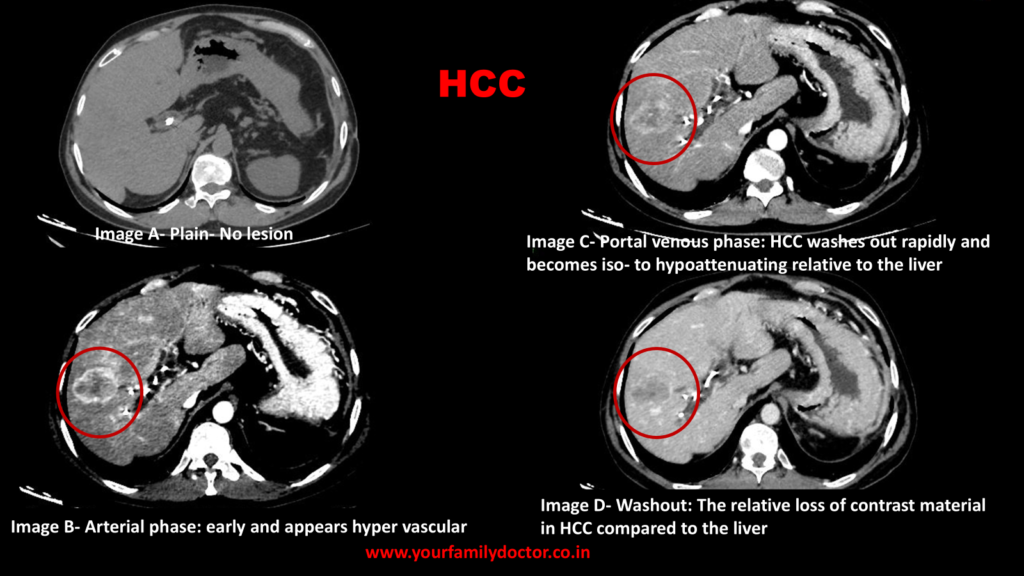

1.2 Computed Tomography (CT)

- Role: Gold standard for imaging in suspected HCC when ultrasound findings are inconclusive. CT scans provide detailed liver anatomy and help in staging.

- Findings:

- Arterial phase: Hypervascularity is a hallmark of HCC. Lesions enhance during the arterial phase due to the tumor’s blood supply from the hepatic artery.

- Portal venous phase: HCC typically shows a washout appearance (hypodensity) compared to surrounding liver tissue due to less contrast uptake in the venous phase.

- Delayed phase: Tumor shows persistent enhancement or hypoattenuation, distinguishing it from benign lesions like hemangiomas.

- A key diagnostic feature is the “rim enhancement” seen in larger tumors.

1.3 Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI)

- Role: Used for detailed evaluation, especially when CT results are inconclusive or in patients with underlying cirrhosis. It provides superior soft tissue contrast.

- Findings:

- Arterial phase: Like CT, hypervascular lesions enhance in the arterial phase.

- Venous phase: Washout of contrast occurs, which is typical for HCC.

- Hepatobiliary phase (using Gd-EOB-DTPA contrast): Tumors may appear hypointense due to impaired hepatocyte function in the lesion, aiding differentiation from other liver masses.

- MRI is superior for detecting multifocal HCC or vascular invasion.

1.4 Contrast-Enhanced Ultrasound (CEUS)

- Role: An emerging tool used in the diagnosis of HCC, especially in patients with poor renal function who cannot undergo CT/MRI.

- Contrasts used

- Contrast agents used are microbubble-based agents. These agents consist of tiny gas-filled microbubbles that are much smaller than red blood cells, allowing them to circulate within the bloodstream and enhance the ultrasound signal.

- They are renal safe

- Eg. Sonovue (Sulphur hexafluoride microbubbles), Perflutren microbubbles, Galactose microbubbles

- Findings:

- Tumors show hyperenhancement in the arterial phase followed by rapid washout in the portal venous phase, similar to CT/MRI.

- Allows for real-time dynamic assessment.

1.5 Positron Emission Tomography (PET)

- Role: Not routinely used in initial diagnosis but can be helpful for staging, particularly in assessing distant metastasis.

- Findings:

- HCC lesions may demonstrate increased uptake of FDG (fluorodeoxyglucose), indicating high metabolic activity.

- PET scans are more sensitive for identifying extrahepatic metastases, including lymph nodes, lungs, and bones.

2. Diagnostic Criteria for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

In the absence of histological confirmation (e.g., biopsy), the diagnosis of HCC can be established using imaging if characteristic radiological findings are present. The American Association for the Study of Liver Diseases (AASLD) has set forth diagnostic criteria:

- Typical Imaging Features:

- CT/MRI showing a lesion with characteristic arterial phase hyperenhancement followed by washout in the venous or delayed phase.

- Nodules that demonstrate growth over time are highly suggestive of HCC.

- Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP):

- An elevated AFP level > 200 ng/mL in the appropriate clinical context (cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis) can support the diagnosis, though AFP is not always elevated in early-stage HCC.

- Biopsy:

- Not required if imaging findings are diagnostic, but may be used in ambiguous cases or in patients with non-cirrhotic livers.

2.1 Role of PIVKA-II in HCC Diagnosis

PIVKA-II (Protein Induced by Vitamin K Absence or Antagonist-II)-Prothrombin normally undergoes a process called gamma-carboxylation, which is vitamin K-dependent. In patients with liver dysfunction (such as those with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis), this process is impaired, leading to the accumulation of abnormal, uncarboxylated prothrombin — PIVKA-II.

PIVKA-II levels are often significantly higher in patients with HCC compared to those with benign liver conditions like cirrhosis or hepatitis without cancer, though it can be even elevated in benign conditions like focal regenerative nodule or hepatic adenomas. But when compared to AFP the elevation of PIVKA-II in benign conditions are less frequent.

Also in early HCC AFP might not be elevated. In such situations PIVK-II has better sensitivity.

Click here to read comparison between PIVKA-II and AFP

3. Management Protocol for Hepatocellular Carcinoma

3.1 Initial Assessment

Before deciding on the appropriate treatment, gastroenterologists must assess the following:

- Liver function: Assessing the degree of liver dysfunction is critical in determining the treatment approach. This is typically done using:

- Child-Pugh score: Classifies cirrhosis based on liver function.

- Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD) score: Assesses liver disease severity based on bilirubin, creatinine, and INR.

- Tumor Characteristics:

- Size and number of lesions: Larger or multinodular tumors may require more aggressive treatment.

- Vascular invasion: The presence of portal vein thrombosis or extrahepatic metastasis indicates advanced disease and may alter treatment options.

3.2 Treatment Options

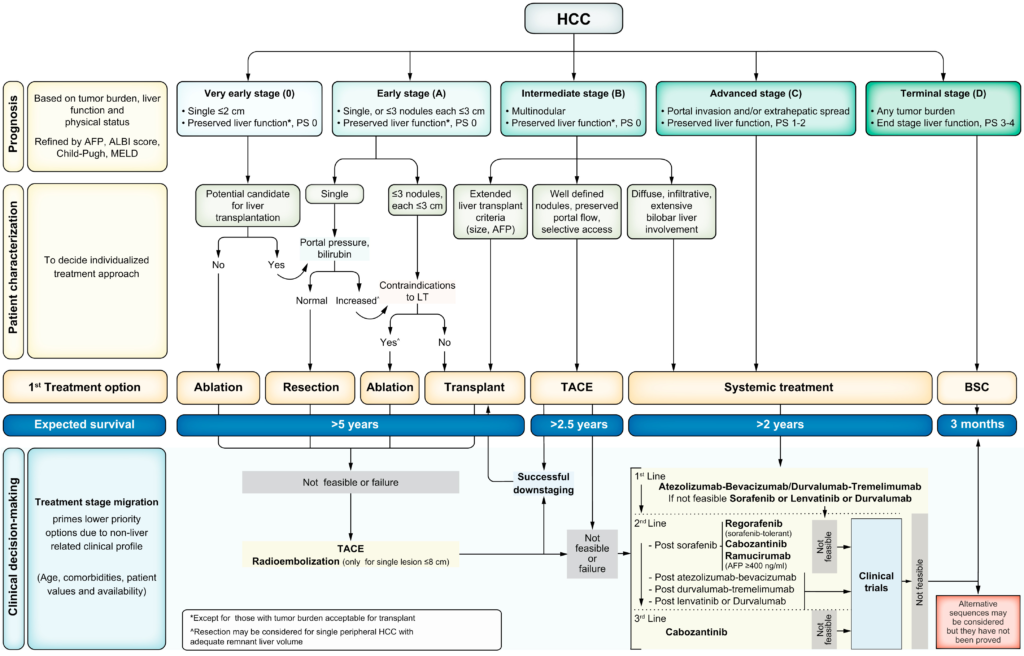

The management of HCC depends on tumor size, number, liver function, and whether there is vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread. Major treatment modalities include:

- Surgical Resection

- Indicated for patients with a solitary tumor and good liver function (Child-Pugh A or B).

- The tumor should be resectable, with no vascular invasion or extrahepatic spread.

- Liver Transplantation

- Criteria: The Milan Criteria is commonly used for transplant eligibility: a solitary tumor ≤ 5 cm or up to 3 nodules, none > 3 cm.

- Transplantation offers the benefit of treating both the tumor and underlying cirrhosis, making it a curative option for selected patients.

- Ablation Therapies

- Percutaneous ethanol injection (PEI) or radiofrequency ablation (RFA) are commonly used for small, solitary tumors (< 3 cm) or for patients who are not candidates for surgery.

- Microwave ablation (MWA) is another option with similar efficacy to RFA.

- Transarterial Chemoembolization (TACE)

- Used for patients with intermediate-stage HCC who are not surgical candidates. TACE involves the intra-arterial injection of chemotherapeutic agents and embolic agents to block the tumor’s blood supply.

- It is effective in controlling tumor progression in patients with preserved liver function.

- Systemic Therapy

- Tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs), such as sorafenib and lenvatinib, are the standard first-line systemic treatments for advanced HCC, offering modest survival benefits.

- Immunotherapy (e.g., PD-1/PD-L1 inhibitors) has emerged as an important option for advanced disease.

- External Beam Radiation (SBRT)

- Considered for patients with advanced disease or those who are not candidates for surgery or ablative therapy.

The updated BCLC strategy for prognosis prediction and treatment recommendation has been updated -2022

Click Here to read more on BCLC

3.3 Follow-up and Surveillance

For patients undergoing curative therapies (e.g., surgery, ablation), regular surveillance with imaging (US, CT, or MRI) and AFP measurements are recommended to detect recurrence. Surveillance intervals vary but typically occur every 3 to 6 months.

For high-risk patients (e.g., those with cirrhosis or chronic hepatitis), periodic screening with ultrasound and AFP every 6 months is recommended by the AASLD.